Trading Suits for Sofas

Generated by Midjourney with the prompt "A sad college student lounging on a couch. Behind the student is a college diploma hanging from the wall. Near the couch are suitcases and moving boxes. Illustration"

Why haven’t historical technological advancements driven mass unemployment with each innovation? The answer to this question has extreme implications for understanding the current AI revolution, and there are answers. The “mass unemployment” is found in prime-age workforce participation rates instead of employment rates. We’re left with another question: Is this another cotton gin, or is it a wholly different beast?

We’ll look at a few things starting with how businesses react to efficiency changes and under what conditions. Next, we’ll look at how those reactions may impact peoples’ involvement in the market and the conditions there. And finally, a hypothesis behind an issue that has been simmering for some time.

Unit Costs and Innovation

So, let’s replay the history. The cotton gin is invented, what happened to two things:

The cotton industry?

The people that were deseeding cotton?

To understand what happens to the industry, we should take the perspective of a capital manager. The capital manager must decide what to do with money, people, and assets when there has been a change in productivity – an innovation.

Efficiency gains affect the supply of a good or service: more apples per acre, more tax filings per hour, etc. As such, the decision a capital manager makes depends on what got more efficient and what the demand characteristics of the market are.

There are two kinds of efficiencies:

You supplied more by being more efficient with your labor.

You supplied more by being more efficient with your physical or monetary capital.

Demand changes are best understood through elasticity. When demand is elastic, changes in the price change the consumption of the good or service. When demand is inelastic, changes in the price do not change the consumption of a good or service.

Per unit of labor time improvement

Inelastic Demand

Reduce the hours worked, hold your non-human capital. Because you’re able to satisfy the market with less time, additional hours only increase supply which reduces price without changing sales.

Elastic Demand

Hold or increase the hours worked and increase your non-human capital. Reducing the price gives you an edge over competitors or other substitutes for your customers’ time/money.

Per unit of non-human improvement

Inelastic Demand

Reduce non-human input, effect on human input ambiguous.

Elastic Demand

Hold or increase non-human input, effect on human input ambiguous.

Per unit of time improvement is what we’re most worried about. Per unit of non-human improvement is typically like I can grow more hay on the same amount of land, or it cost $10 per hour to run a gymnasium’s worth of vacuum tubes but now it’s $0.01 per hour and there are 1 billion transistors on a chip the size of a thumbnail.

Capital manager cap on. The cotton gin was invented. It doesn't make more cotton sprout from the ground, but you don't need to spend nearly as much time deseeding. Does the market crave more cotton? Is it a market maker where a surplus can create downstream markets? Do I buy up a bunch of land, move some people whose time has been saved over there, and drive the current price down? Well, let’s see what history says.

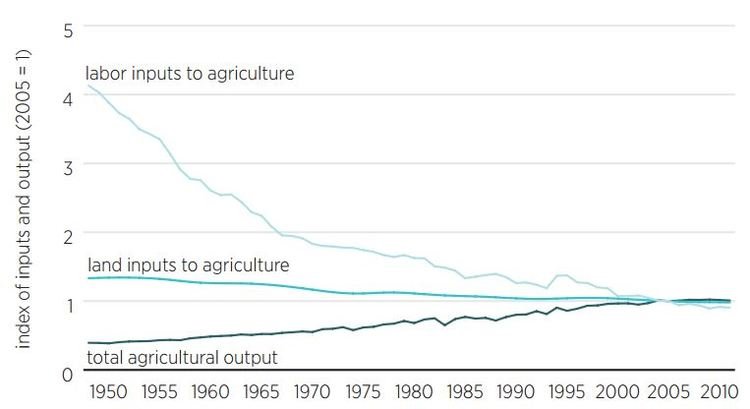

This obviously isn’t the time frame for Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, but it paints the picture of innovation in agribusiness. It's comparing the quantity of each input category to its 2005 level.

Source: Jayson Lusk, USDA

Slash the labor input. Simultaneous innovations in non-human capital afforded efficiency gains in land use as well. The labor market for agriculture is outmatched by innovation. Similar tales can be told about the labor market for manufacturing.

The Pitfall of Freeing Up Time

It's at this point that some silly people – mostly economists and yogis – go, "And then they had time to explore other things and generate new domains of value through their creativity!” Some have referred to this hypothesis as the “Cognitive Surplus”. The idea lacks context and depends deeply on words like ‘can’, which I will revisit. The notion that a cognitive surplus is a positive thing hinges on whether that free time is utilized for productive purposes. The evidence for this is conflicting. We know very, very, very well from sociological research that men without work create big problems for the communities they reside in. I emphasize this point because the assumption that "people come up with other productive things to do and most people whose labor was nullified and have time will be valuable in those new roles" is an extremely consequential and dubious assumption to make.

Warning aside, the historical trend was indeed the time surplus being utilized for many other things. People not working the farm could work the factory. The factory created some home appliances, and next thing you know the women formerly busy keeping the shack livable had time to enter the labor force as well. Now instead of even buying and cooking your food you just pay someone for the cooked food, assume a tax for waste management, and skip the dishes altogether.

What was this new value each wave of innovations allowed? Well, in the beginning, it was about saving time. A family’s time was consumed with keeping the lights on. It’s not particularly complex to water fields nor to clean the dishes, but they are pretty darn time consuming and very important. Those innovations gave time back to people who could profit from it, and that time surplus could be used to generate time savings for other people strapped for it. It’s much easier to continue that chain when there is a very specific force for demand:

People elsewhere strapped for time and capable of paying for some of it back.

Today, people tend to not have time because they expend much of it working for wages, not attending to unprofitable matters like dishes. 56% of the population are paid at hourly rates. But per unit of time improvements reduces the time required to produce a unit, so between layoffs and time cuts the total number of hours labored will decrease (unless the marginal cost reduction makes downstream goods or services feasible). The hourly laborers whose work became more efficient will have more time and less capital, a counter to our force for demand.

The salaried folk are a tad different because there isn’t a gradient of time. Instead, it operates as a step function. If the price of the efficiency gain equals a salary, and the market is inelastic, managers can layoff. If the market is elastic, you have gained a new hire’s worth of work without paying a whole new salary.

Returning to the cognitive surplus’s dependency on ‘can’, there isn’t a strong case for “people are strapped for time” anyways. We in the US spend a lot of time on leisure. There has also been a lot of surplus capital sloshing around, so that free time could be used to spend and that spending drove job growth to service their activities. But what do people spend their free time doing nowadays? Things that require human intervention that would require a proportionate number of jobs? No, per the BLS it’s mostly TV, computers, and hanging with friends – two of which don’t drive direct value and both of which scale well with automation. The former two’s value is in connecting viewers with surplus capital to producers looking to sell – marketing and advertising. But the viewers don’t have the surplus capital that they previously did. Perhaps don’t spend as much trying to find customers? Now we’re cutting into the salaried workforce.

Point is, the time is already available and is ours to profit from, but it wasn’t being profited from to begin with. Perhaps someone else can point to other conditions, but I see two that stymie this:

Unit cost reductions make downstream goods or services feasible/profitable.

Surplus capital concentrates amongst fewer people, however their spending “velocity” mirrors that of many people with a little bit of surplus capital.

I’m pretty sure point 2 is wrong, but fractional banking makes the answer more complicated. Point 1 seems like a total rabbit hole and woefully dependent on the industry. Falling unit costs of transistors and energy has allowed for energy and compute/memory inefficient software to rise. But this is a non-human capital efficiency improvement. More transistors on a wafer in addition to more abundant energy doesn’t fit the “time savings” model that drives the information industry.

Not All Time is Equal

I don’t know why I keep hearing this argument or why people even believe it, but not everyone’s time is equal. This isn’t a “finance quants get paid more per hour than basket weavers” argument. No, this is a “finance quants could probably do basket weaving if they had the time, but a basket weaver probably couldn’t do quantitative analysis in finance if they had the time” kind of argument. It’s been known for over a century now that there are meaningful differences in the cognitive abilities of humans. It’s been known for decades that these differences are resistant to interventions in parenting or education. The proof of this in the real world can be seen in the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of job training programs.

The whole idea behind job retraining is that someone whose time was no longer needed can be taught things that make their time needed again. Throughout the training literature, whether in the US or in another Western nation like France, the inadequacy of this approach is put on display.

I am not saying that people cannot and will not learn new skills to generate value. I am again cautioning against assuming that will occur to a sufficient degree. We are not prepared to retrain at such a scale, and this transition will happen faster than any that came before.

Next Victim

The above commentary has focused on previous technological transitions, transitions that affected a labor demographic that we call “blue-collar”. Moravec’s Paradox is a robotics observation that it is way easier for a machine to “reason” than it is to interact in the physical world. Most of what’s left of blue-collar labor requires a lot of work on-site and on the fly. The construction workers will be fine, so who’s on the chopping block? Well, your average college graduate of course.

There has been a complaint floating around for as long as I can remember: “college didn’t teach me anything related to my job”. Well of course not. Coming out of college you know basically nothing about an industry nor how to work within it. All your employer did was get you to pay the university to prove that you possess a minimum capability to succeed at things that require some thought. The credential really isn’t about knowledge, and that’s a problem of its own. College graduates mostly know nothing. Most of what they do know is either common sense or learnable after doing it for 9 hours a day, 5 days a week, 200+ days a year; the rare graduate put enough time into Excel coursework to outcompete the person that toyed with Google Sheets in their free time. A 3-credit hour, 12-week course is going to come out to almost 40 hours in the classroom, maybe another couple hundred or so outside of it depending on their conscientiousness. A few hundred hours is a good student’s head start from that course.

This begs the question, what do those entry-level white-collar jobs do? To be blunt, they get the scraps that senior persons don’t have time for. There’s almost always somebody else within the company that could do what the newbie was tasked with, but their time is better spent elsewhere. What the emerging AI tools allow those senior people to do is complete the task almost trivially, no junior being paid tens of thousands of dollars.

I’ll draw two recent examples, both related to my own work.

That was quicker than expected...

There was an anomaly in a client’s website visitation analytics. I wasn’t particularly busy and was asked to check this out by client-facing personnel. In most cases, to find out what’s going on here I would have read dataset documentation, compose database queries to fetch and investigate that data, and perhaps create visualizations to audit the query or try to get a bigger picture. There’s almost always a mistake somewhere so you need to do some digging. I started with some simple queries I knew off the top of my head to get the basics, and then hopped over to Google. A few clicks into Google Analytics and something new popped up. A search bar accepting prompts. I typed in the kind of visualization I wanted, Google created it, and there was my answer. Quick, easy, done. Respond to the client-facers and explain what I found. Back to some old problems that were on the back burner. No need to dig into table schemas, date formats, or query language dialects. No need to punt it to anyone else.

10Xer

All of 2023 has been a race trying to keep new developments flowing while attending to impromptu tasks for clients. Before March I was worried that we may have to hire another junior data engineer. There goes another stack of cash. But at the dawn of April, I subscribed to GitHub Copilot X. I cannot emphasize how much time, cognitive strain, and frankly patience this tool has saved me. It has plenty of flaws, hiccups, and limitations, but if you have experience in the language and understand the big picture of the program, then you can spot and amend those with ease. Instead of banging my head against documentation pages or trivial code typing, I can focus on the architecture and flow of the program such that it fulfills our business requirements and vision. What could have been an introductory job or internship to help a newbie learn the language, learn analytics engineering by example, and get some experience was snuffed out by a cheap subscription. I am one person. Scale events like this out and you must ask, “How many college graduates will actually be in demand?”

Water cohesion, but you run out of water.

It’s here that we finally get to my concern. I’m not all that far into my own career, but the progression of generations “up the totem pole” seems a lot more like a water up a straw. Bob is taking on new responsibilities and needs someone to take care of a few others, so he looks to Joe who has done well with Bob’s other scraps. Or maybe he hires Sam, who was successfully dealing with Mary’s scraps. Or maybe Bob hires Lindsay who already knows the ropes and wants a change of scenery more than a change in responsibility. No matter where Bob’s responsibility successor is coming from, they learned the other ropes somewhere. When sipping from a straw, water follows water.

But what happens if there aren’t that many people learning the ropes? Or maybe the jump between ropes gets wider? Well, you can try to raise the offer salary to snag a Lindsay, but sometimes that’s just not feasible. Do you risk relying on someone who just cannot accelerate quick enough to close that gap?

A complaint many people in my generation know well comes to mind:

“It was an entry level job, but they asked for 2 years of experience in X, a master’s degree, experience in tools Y and Z, and 1 year of industry experience.”

The greatest cost of the AI revolution will be found in the experience gap. Per unit of labor time improvements have already made the zero-to-one problem for careers more difficult, and blue-collar sectors have been living in a skills shortage for a while. I’m reminded of this panel where the defense industrial base is struggling to find adequately trained laborers to scale up production to meet wartime consumption rates (which are consistently underestimated, not to worry you).

Final Thoughts

I don’t have anything close to a solution. The objective of this piece was to lay out the dynamics behind a problem and articulate it more clearly. Innovations in labor time are harmless under certain conditions. These conditions include:

The market demand is elastic.

People with surplus cash have time to spend it with.

Human time is a commodity.

Without these conditions, there will be people whose time cannot be utilized. This has always been a problem. There are valid reasons to doubt these conditions hold in the modern economy. Adaptation within the workforce is possible, but the rate at which this can occur is uncertain at best, insufficient at worst.

The population at most risk is the one without experience and whose early career is dominated by performing the menial, yet educational, tasks that experienced personnel do not have time for. Chief amongst these are college students. The debt accrued by college students whose time is becoming commoditized raises the stakes for our financial system and its future.

Extras

“Elastic”

I drop ‘elastic’ and ‘inelastic’ around as if they’re discrete. They are not. This is a rhetorical convenience. The degree to which a market is one or the other will influence its sensitivity to unit of labor time innovations.

Gradualism

When I took the perspective of the capital manager, I framed the issue as the innovation occurs, the manager sees the innovation, the manager reallocates the resources. This is another rhetorical convenience. While an innovation may prompt immediate action in some cases, more probable scenarios are that the cotton silos are overflowing or there aren’t enough tax filings pending to justify having a person onboard let alone hiring another.

Prompt Engineer is the new Search Associate

I thought the people talking about a “prompt engineer” were joking, but apparently not. Google did not create a “search associate”, it just cut out a middleman in the information distribution sphere. The amount of information that must be conveyed from the knowledgeable person to the “prompt engineer” might as well be the prompt. If the former doesn’t have time to resolve the errors, hire a more junior person to tidy up prompts or results in between learning the industry and grabbing the staff coffee.

Marc Andreesen on AI and Unemployment

Came across two articles of his (1, 2). He emphasizes the machinery chapter of “Economics in One Lesson” by Henry Hazlitt, and then cites a petition to the French National Assembly by Frédéric Bastiat. I hope that this article articulated that the conditions that allowed Hazlitt and Bastiat to be correct one and two centuries ago should not be assumed for the present.

The Free Time Market

A sector that I downplayed in this post are the industries that supply things to do with free time when there’s surplus. This includes travel, media & entertainment, food & restaurant, sports, and others. While markets can emerge or grow thanks to labor time innovations, their demand is contingent on that surplus. If the surplus shifts towards people without free time, and free time towards people without money to burn, then these industries shrink.

The “exceptions” are the markets who charge in time. This idea was cursorily mentioned in the post, but I will reiterate here. Facebook is free, but it capitalizes on businesses seeking potential customers with surplus. If time or surplus diminishes within the user base, then cost per acquisition goes up due to lower conversions and the business withdraws marketing and advertising dollars. Companies like Facebook are enterprise-facing, and their value proposition is their user base. Users without time to spare or money to spend aren’t very valuable to the customer, and thus Facebook suffers alongside their daily active users.

Social Prestige

One of the many factors that drives students to colleges is the social prestige that accompanies a college degree, not the skills or knowledge that the institutions possess. The same motivation applies to white-collar work. An inability to attain or leverage those ostensibly prestigious achievements seems to create problems of its own. I aim to explore this in another post.

Monopoly Markets

Addendum: April 29, 2023

I reasoned that capital managers are incentivized to maintain an existing supply when demand is inelastic. The exception to this is in markets where monopoly is tolerable. What the efficiency gain allows is a price range where the company maintains a profit, but competitors operate at a loss. Predatory maneuvers such as this would incentivize the manager to maintain or grow the capital where efficiency developed, whether that be land or people. The growth in market share allows the company to have higher gross profit in the long run.